Arthur Rothstein: Photojournalism

Photojournalism textbooks started here and follow this format

You were probably wondering when the next installment of my newsletter would drop. Me too. When the school year ended, I was hopeful that I would be organized and on top of this project. Due to working full-time at my summer job, I have had a hard time finding the energy and mental focus to write on a consistent basis during the work week. Family commitments have also kept me from writing. I want to say that these are excuses, but I need to keep food on the table, bills currently paid, and a roof over our heads. The weekends are when I have time and the space in my brain to work through these ideas.

My goal is to summarize the book, touch on important points, highlight photographers I had not previously known much about, and give an overall conclusion of the book. What has happened as I have gone through this first book is that more books by photographers mentioned have come from the library as way to dive deeper into the topics at hand. At the moment, I have nearly 50 books checked out or requested from the university library. This has become a summer ritual for me. I tend to dive into things in the summer when my brain is able to digest new ideas.

Photo books were my gateway into photography. I have participated in an unhealthy desire to collect. I have judged others on their book collections. With age, I have gotten to the point in life where I know buying a particular book will not make me feel better about myself, even if it is a magnum opus of a photographer I have much admired. The library has been kind enough to add the books I have requested to their collection. My first thought is now to check the library, which makes it easy to borrow from other University of Wisconsin System schools. I have also taken advantage of interlibrary loans when the system does not have what I am looking for.

The goal for this newsletter is for me to gain a greater understanding of what some textbooks are like for photojournalism and how they compare to more general photography, or art photography book (that may or may not be considered a textbook). This idea came out of a need to find a text for my classes, that would be beneficial to the students. My background is in photojournalism and I have been teaching in art-based programs longer than I worked for newspapers. You would assume I have fully crossed the bridge from journalism to art, but I am reluctant to. Hopefully, this project I have rattling around in my head will help me in the journey and let go of my past a bit more (or at least understand some of the biases I have). I forgot how hard it is to write. This first installment has taken me a lot longer to write than expected. With time and practice, future installments will be better and appear more consistently. That is the goal.

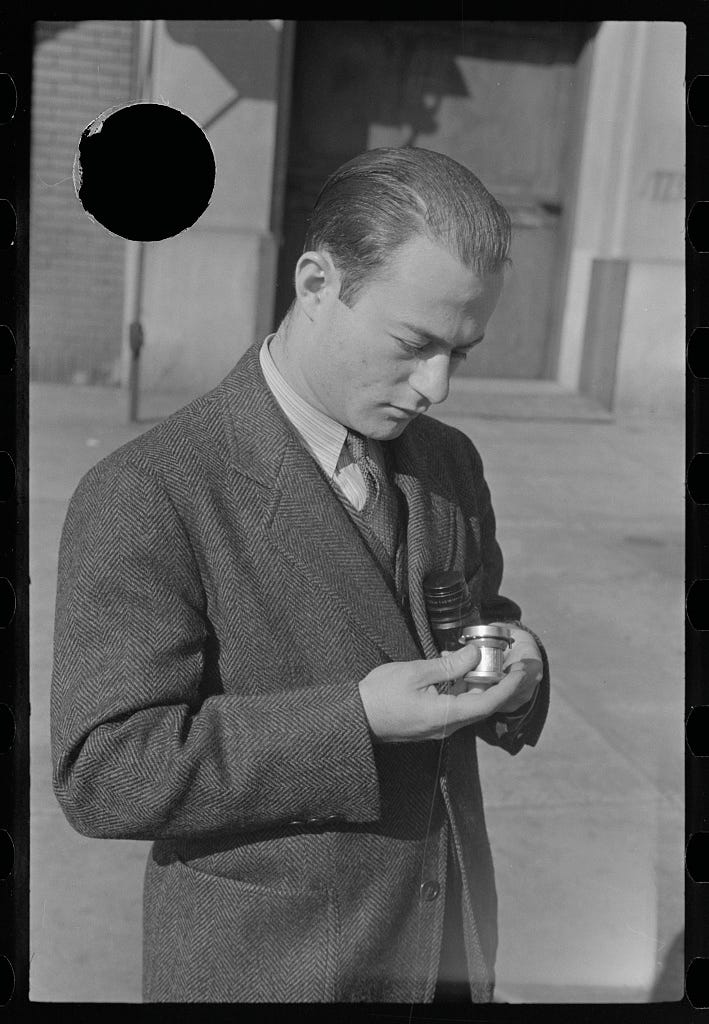

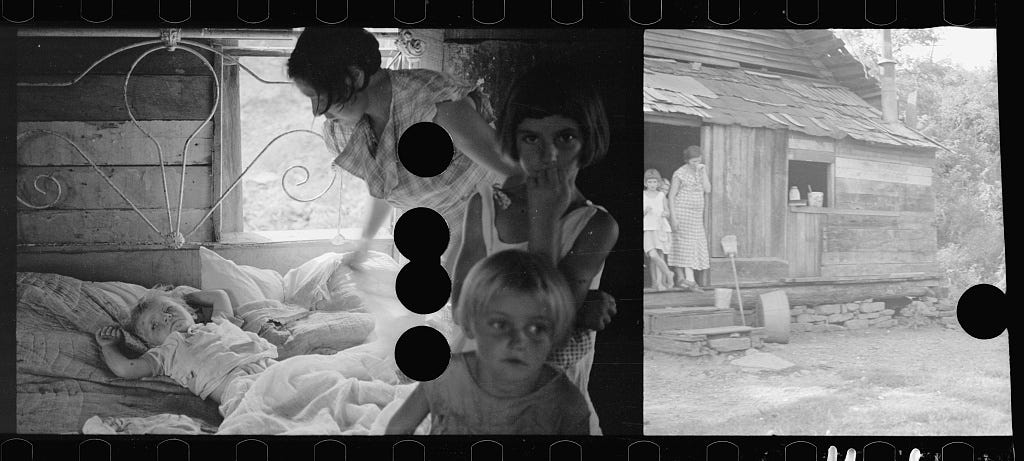

Arthur Rothstein is up first, with his book Photojournalism, which was first published in 1956, making it the first book devoted to the topic. I was able to get the third (of three) edition, which was published in 1974. I believe I read the second at some point in the past, the cover looks familiar, but I am not sure. If I wanted to be a stickler I would get all three editions, but I decided to not be that particular stickler. Rothstein was involved with the Photo League, he also was Roy Stryker’s first hire for the Resettlement Agency (which became the Farm Security Agency). After the FSA, he worked at Look magazine. When that closed, he went to Parade. Rothstein was an early player in the ASMP. Needless to say, he had the experience to write a book entitle photojournalism. The book approaches photojournalism from the perspective of a magazine photographer, but wire services and occasionally newspapers are mentioned.

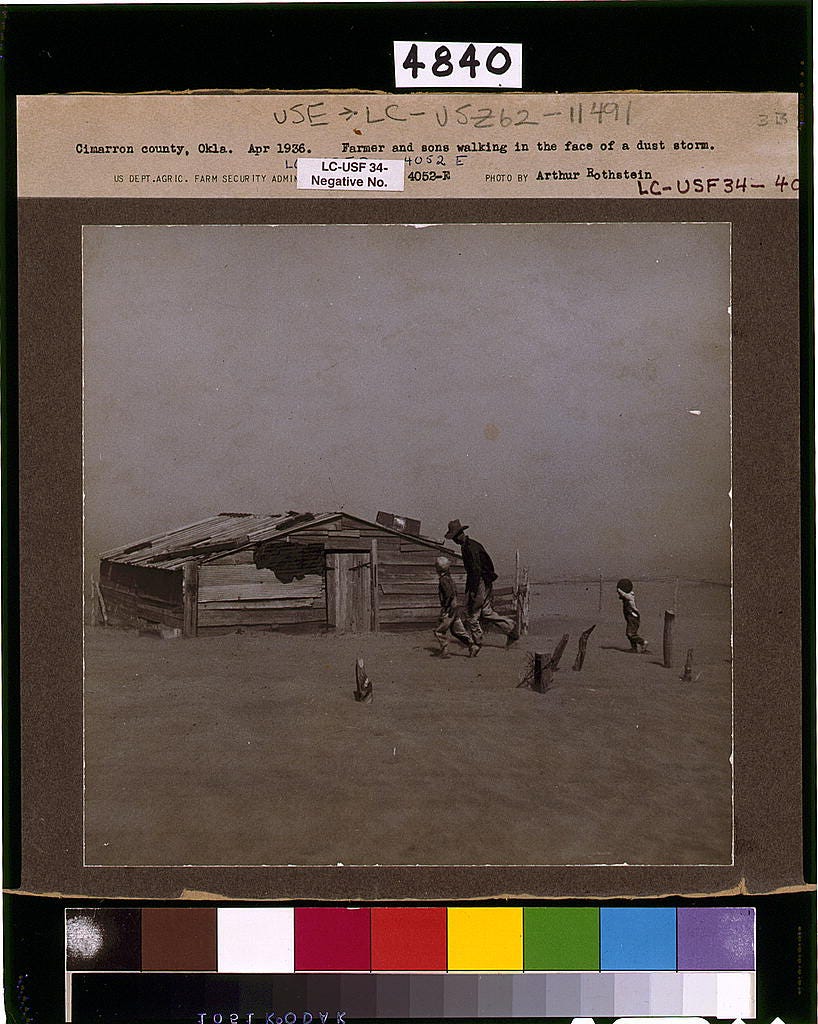

If he came across a frame he did not like, Roy Stryker used a hole punch to clip the negatives so it could not be used. Lewis Bush put some of these together into a zine. I am going to say the four notches in the above photo must mean he was not in a great mood when he was editing this film of Rothstein’s. It is pretty amazing to me that they actually kept the punched negatives.

In terms of the book, Rothstein comes to the point quickly in the introduction. These three pages lay out his views on what it takes to be a photojournalist. “The process of communication is so complex and expensive that to justify the cost and effort, the photojournalist must have something important to say and know how to say it. Above all, he has the power, duty, and privilege to bring light to a darkened work, the light of understanding.” Bringing ideas in that anticipate the news is critical. Without ideas, there is nothing to photograph.

The fact he touches on the emotional idea that a photojournalist can go and bring change to an important topic, and be the realist in terms of the costs of a story in a couple of sentences shows his bias as an editor, rather than the photographer. That is his perspective, which he holds consistently throughout the book.

He also stresses the idea that photojournalism is about communication. “To those who practice this form of communication, the photograph is but a means to an end. This end is publication.: the mechanical reproduction of the photographic statement so that the largest possible audience is reached…The important and outstanding consideration is that the photograph is not the final effort; the publication is. This inevitable adjustment to the requirements of the printed page has created photojournalism and given its practitioners their limitations, disciplines, and greatest satisfactions.”

These points stood out to me for a number of reasons. During my newspaper career, there were times when I could make the picture I knew the paper wanted, then I would make the picture I wanted that was usually more subtle or layered (not a clear summation of the story, but visually interesting) and I would care more for the picture that satisfied me more than the one that satisfied the needs of the publication. This practice seemed to be passed on via word of mouth more than anything else. You did not want to consistently be on the bosses firing line, but you have creative needs that must be satisfied. Rothstein is saying my job is to end up with the best-communicating picture in print. That is the goal of a successful photojournalist, to have your work printed. If your work is not printed, how are you able to communicate?

Taking stock of how I used to work, had I made more communicative pictures than subtle ones would my career might have been better off. This clear-eyed attitude of Rothstein helps me to see the difference between the idea of photography as communication compared to photography as personal expression. There is a difference. To be successful at either, you need to have an audience.

Rothstein the career prospects related to journalism. “The sensible free-lance photojournalist knows that show leather is more expensive than film.” This phrase is mentioned more than a few times in the book. In 1974, this might have been true, but the cost of film today might equal shoe leather.

Rothstein has 10 requirements for the photojournalist:

A broad general education providing a knowledge of physics, chemistry, sociology, languages, history, and geography.

A social conscience that implies a liking for people and an appreciation of how they live.

A sense of adventure that combines the desire to go anywhere and do anything with an enthusiasm for the most trivial assignment.

A constant interest in books and magazines on photographic and general subjects.

An understanding of the mechanics of photography.

The development of an individual style.

The skill to report with as well as pictures.

A knowledge of art, composition, painting, and rapid sketching.

The ability to feel emotion, yet remain objective.

The maintenance of good health; an alert mind and body that react quickly to the unexpected.

Later in the book he describes the ideal news photographer as one who “…No matter how routine the assignment, he never makes the cliché photograph, for his mind is always full of fresh ideas….he never lines up with the hacks who travel in packs…He is consistent, reliable, and brings the same amount of enthusiasm and effort to every assignment, no matter how trivial it may be!” Think about what is being stressed here, always make fresh pictures with your own style, and be enthusiastic about the boring and seemingly dull assignments. Also, when Rothstein is describing someone in the abstract, it is always a he. When I read this description of a news photographer, I immediately think of Yunghi Kim. If you are not familiar with her work, this interview is a good place to start.

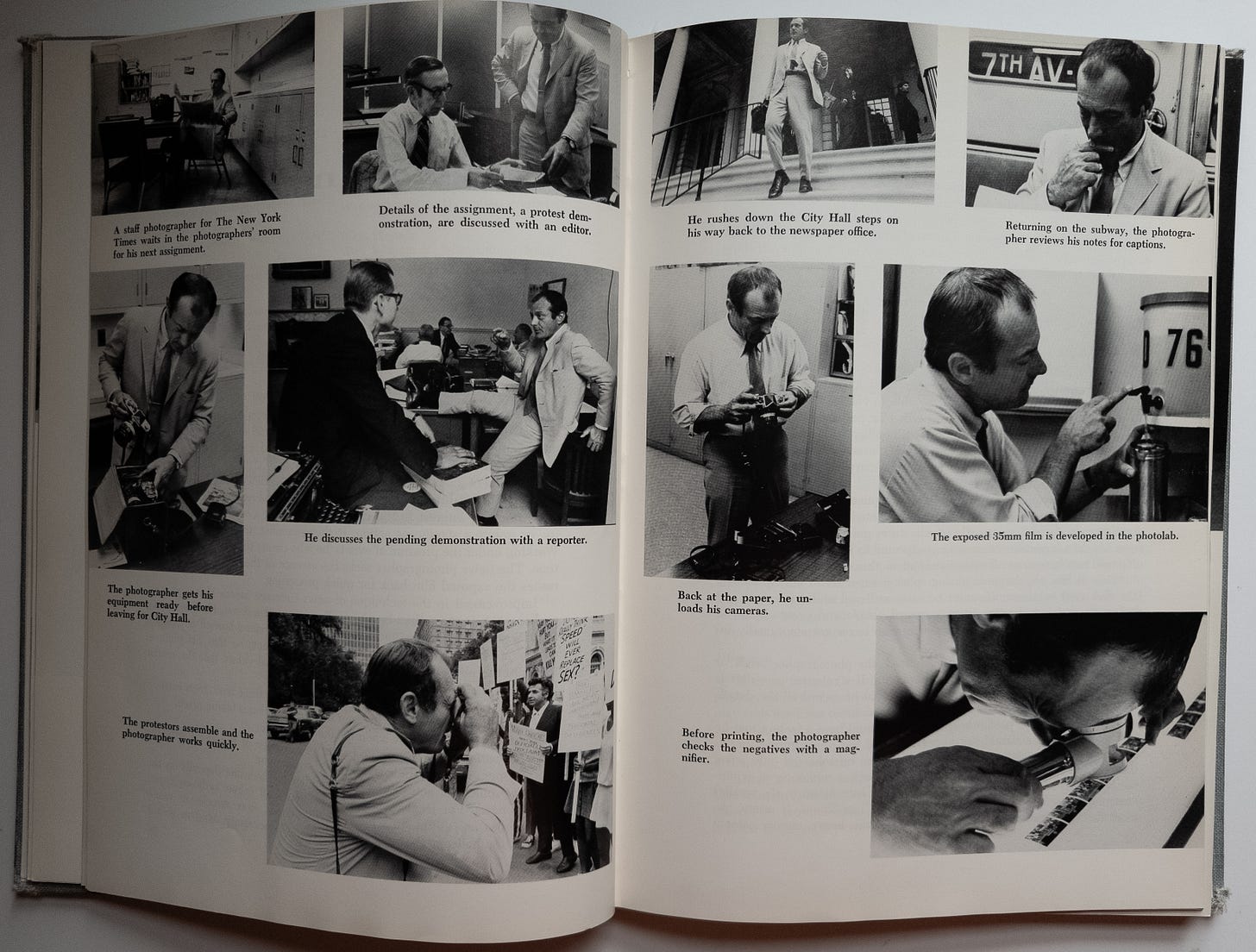

It is in the chapter about the news photographs, there is a two-page spread of pictures following an unnamed Neal Boenzi of the New York Times through an assignment. The reader does not get to see the pictures he produced, which is too bad. Boenzi was the definition of an old-school, hard-nosed big-city news photographer.

Rothstein draws a line between the news photograph and the feature photograph. There is a fair amount of emphasis put on the news photograph, with many Pulitzer Prize-winning examples from the wire services. While he did not discuss the idea of composition yet, it is in discussing the feature photograph that he presents his formula for successful photographic composition.

“…the only valid formula for composing photographs is to perform two voluntary and deliberate actions—select and stress.

The selection of the image may be influenced by three conscious efforts. One of these is the viewpoint. The camera may look up or down; it may observe from a distance or closeup. Each point of view changes the composition of the picture.

The second factor of selection, perspective, is controlled by the lens. A wide-angle lens produces a different composition from a long telephoto. Through his choice of lens, the photographer can vary the arrangement of the elements of the picture in relation to each other.

Finally, there is the moment of exposure. This may determine the position of the subject, especially if action is involved.”

Gilles Peress describes this similarly: “…the photographer is an author because he decides on the moment, but reality speaks extremely forcefully, it is the main author of images. I think the camera is also an author. The Leica with a 28mm lens, for instance, has its own peculiar voice.”

I included the Peress quote because I see it saying the same thing, just differently, more abstractly.

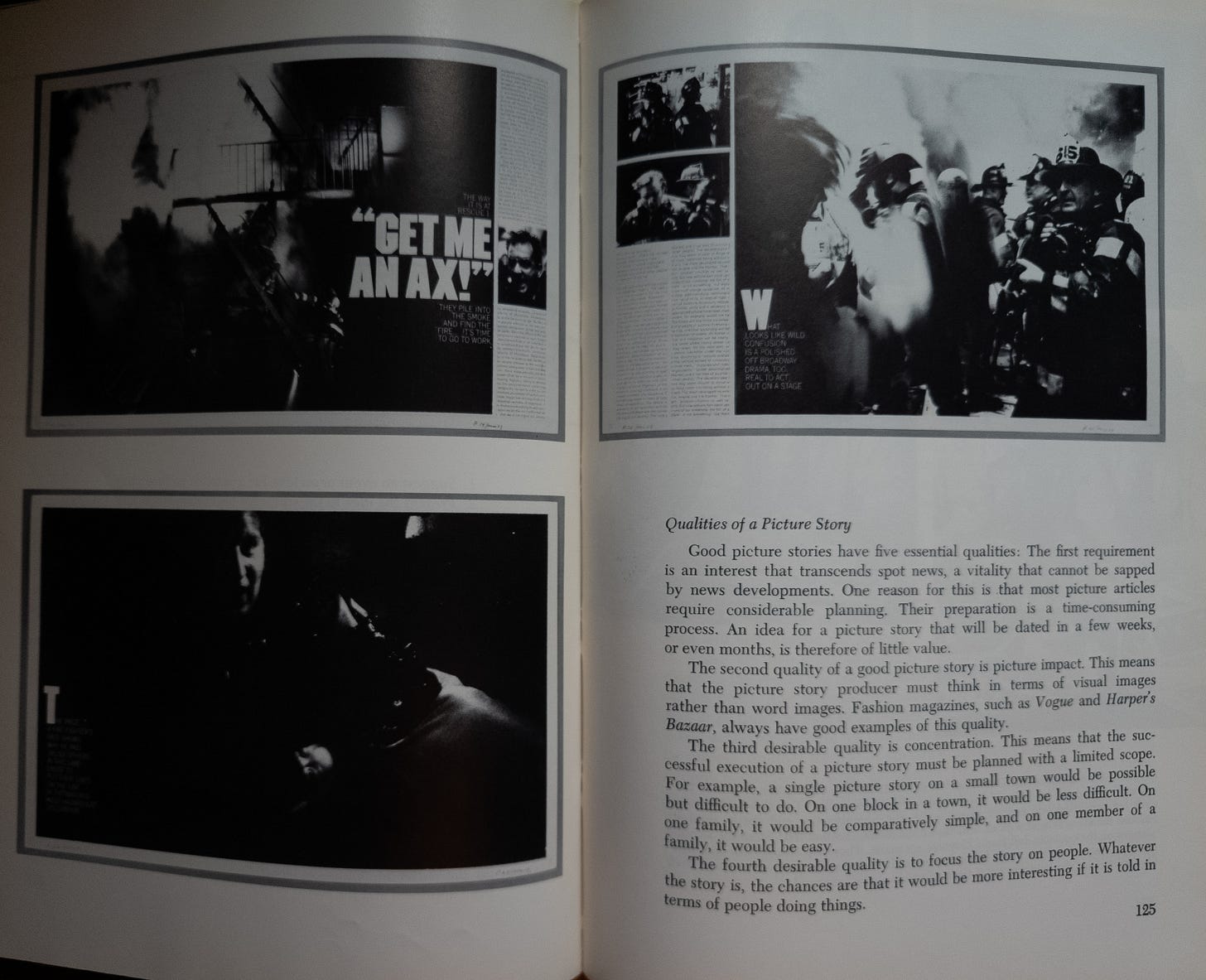

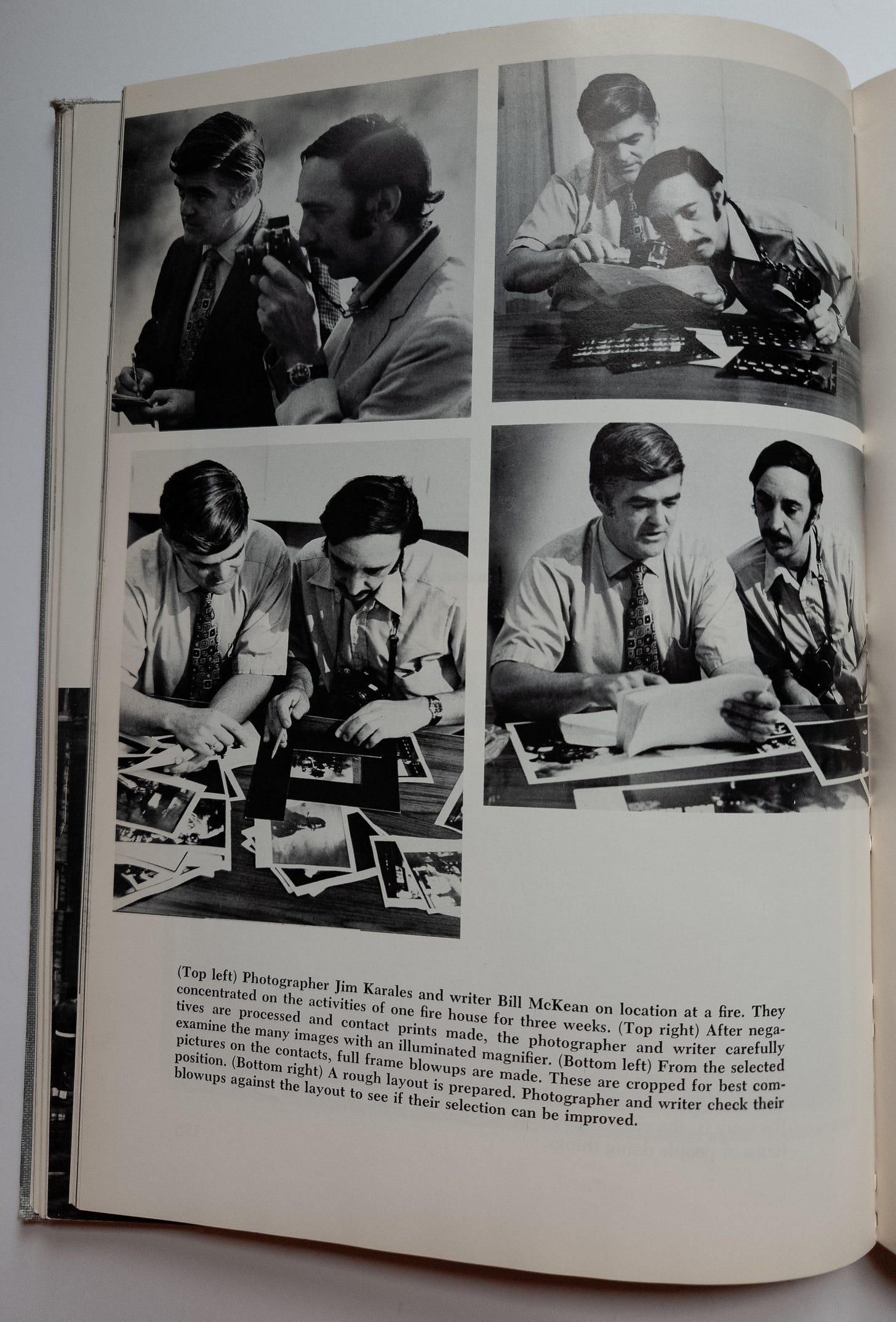

Rothstein talks about working with multiple pictures in two ways. The sequence and the essay. The difference is the sequence shows a singular event in a number of pictures sequentially. An essay is more open to interpretation. Different examples of what he considers photo essays to be are included. All are from Look magazine.

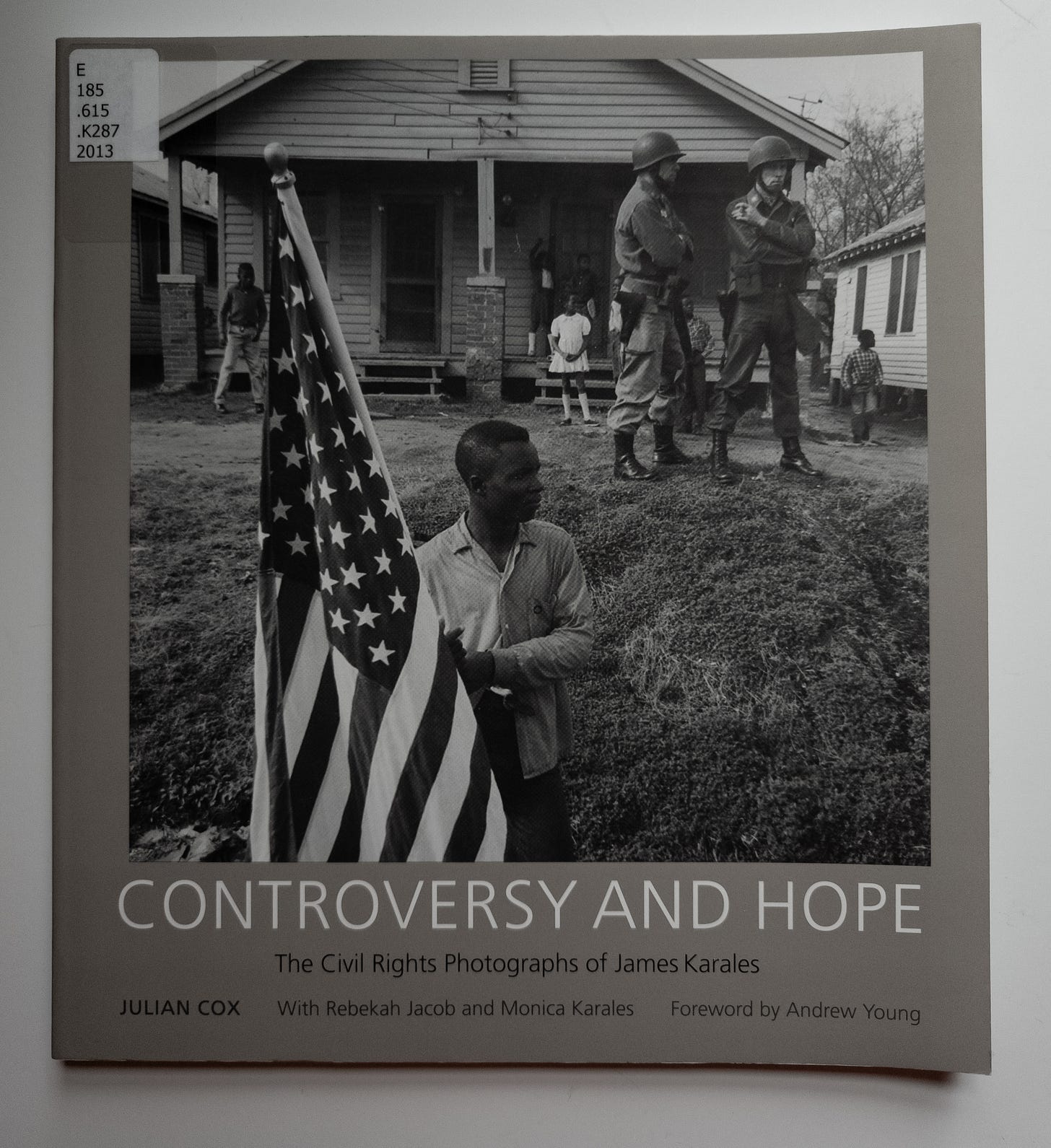

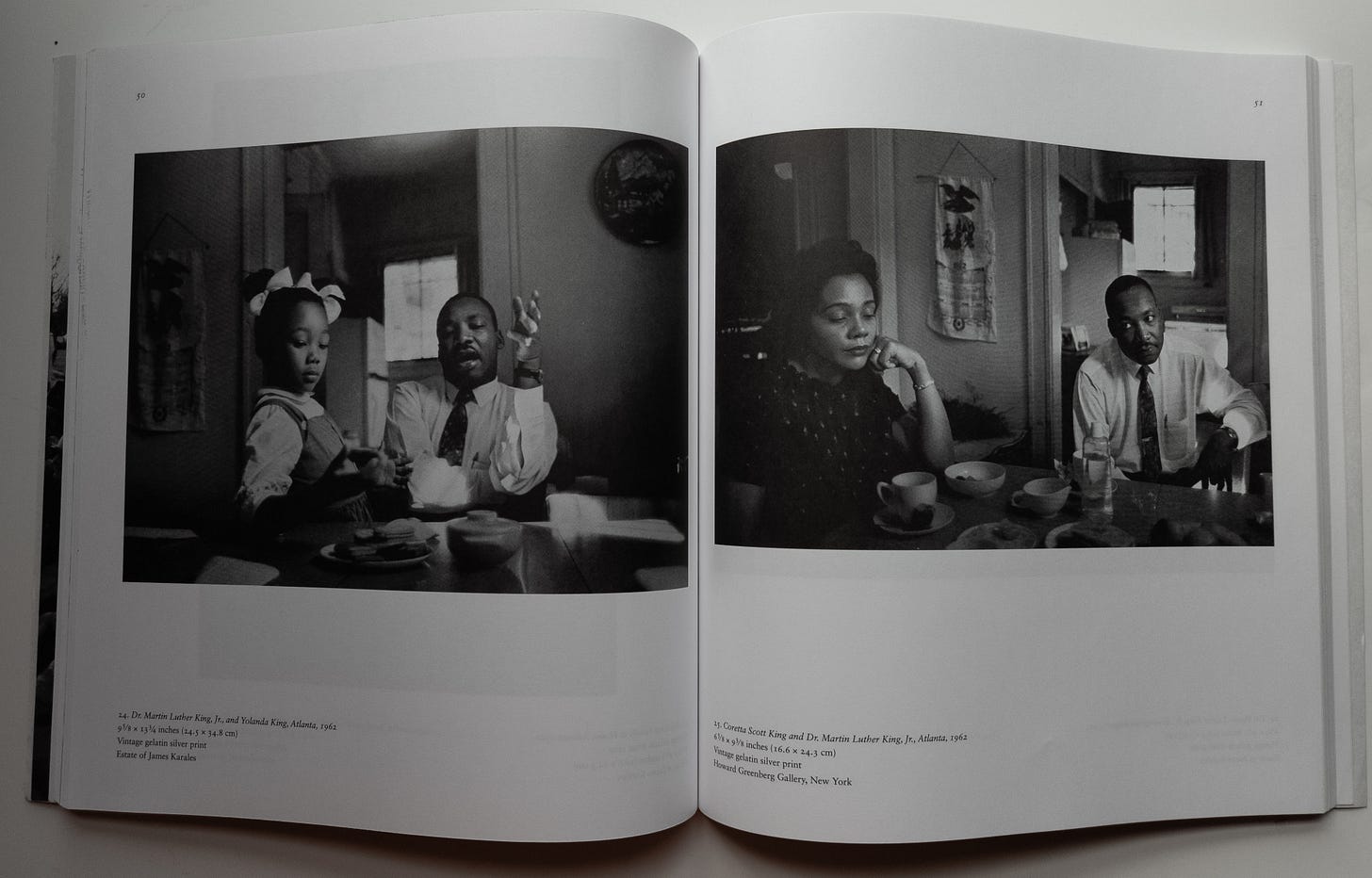

James Karales’ name sounded vaguely familiar to me. A quick search reminded me that he was the darkroom assistant to W. Eugene Smith whom John G. Morris hired. This post by Harold Feintsein is interesting because it gives you an idea of how many prints were needed. I was able to check a copy of Controversy and Hope out of the library. This book focuses on his work covering the movement for Civil Rights in the South. There is another book of his that shows a wider selection of his output, but I have not seen it in person.

Karales’ work is represented by the Howard Greenberg Gallery and the Rebekah Jacob Gallery. The estate also has an Instagram account. The more I go through his work, the more I can see the influence that Smith had on him.

The highlight of reading this book was rediscovering the work of James Karales. Exploring his work has been joyful. It has also shown me how much I have been influenced by the Time/Life canon of photographers. I knew that Paul Fusco and Stanley Kubrick both worked at Look, but Karales’ work has interested me. I am familiar with the work that Bruce Davidson and Burk Uzzle have done during the Civil Rights movement.

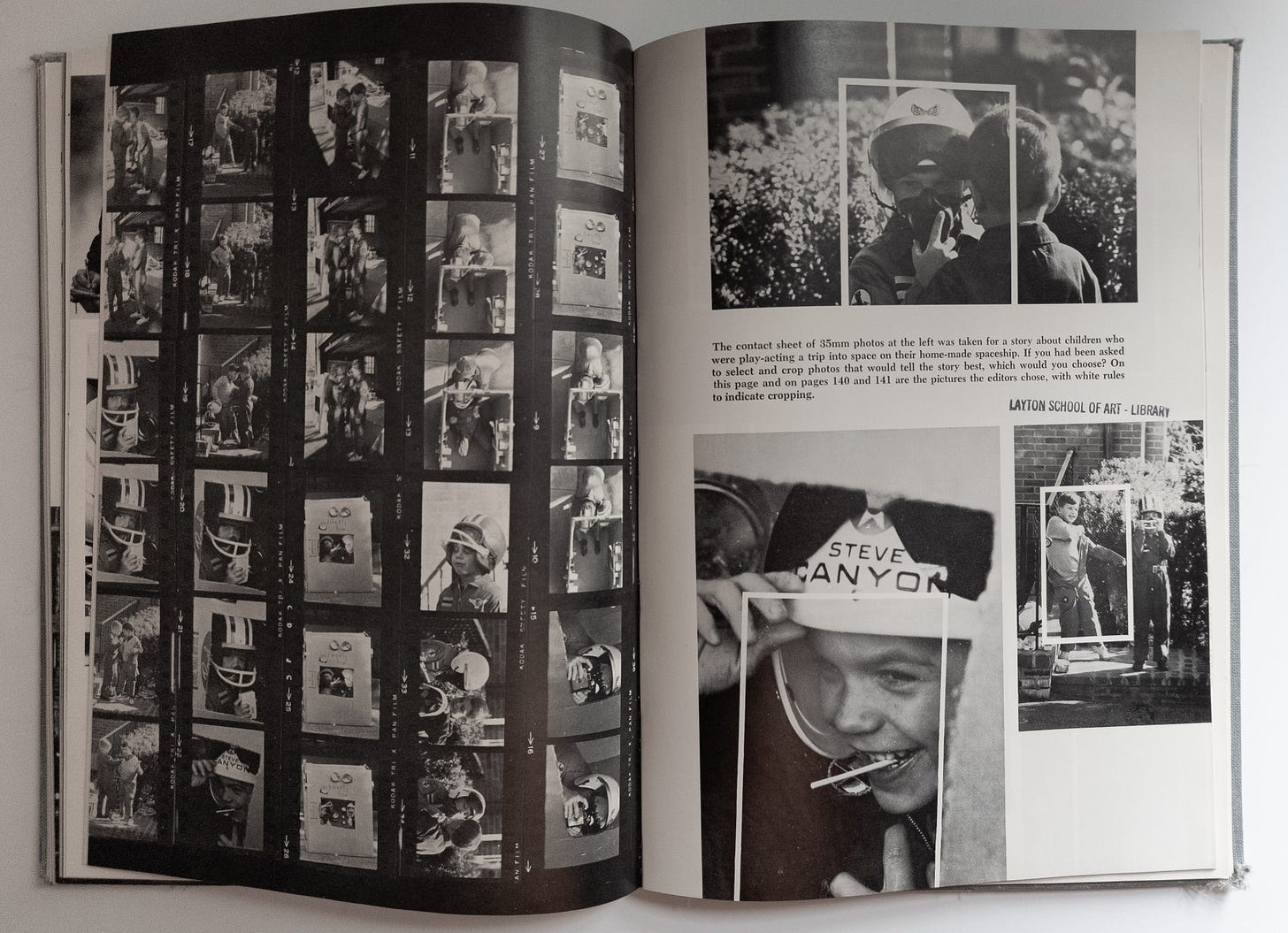

After the picture essay chapter, there are a couple of chapters dedicated to picture editing and display. These chapters get to the heart of the working photojournalist reality daily reality and how being flexible when it comes to cropping is important. There was a phrase I remember hearing a lot during my time in photojournalism school, “Right is tight!”.

Examples like this are something I don’t usually see in a general or art-based textbook. When it comes to cropping, I have contradicted myself in the classroom many times. If I am teaching a journalism class, I stress filling the frame with all of the necessary information. If a crop is needed, I suggest it. When it comes to the art classroom, I am more hands-off and I encourage students to choose a different frame that won’t require cropping. All of the above crops in white are emphasizing the face but at the expense of the context of place (in my opinion). I tend to default to a more traditional storytelling framework of wide, medium, and tight.

The chapter continues with an overall survey of the photography that was present at the times of the writing, but is no longer. It ends with a humdinger of a list of 101 potential story ideas from a seminar of the American Press Institute at Columbia University. Highlights include: 10. Short skirts—everyone likes to look at legs. Photographers were asked to shoot young ladies in mini-skirts and maxi-skirts, and so on. 29. Most newspapers with staff photographers often do not share the opinion of what is the best picture taken on a given story. Once annually it might be interesting to let photographers do the editing—and print a page of the “best picture I've taken that didn't see print” pictures. (It takes a strong editor to permit this.) 52. A day with a camera in a kindergarten class or orphanage. 60. Women at an exercise class. There are some good ideas on the list too, but it feels pretty dated, and sexist in places.

Technical issues related to cameras, lenses, and printing are explained in the book. In terms of lighting, he is direct. “…lighting should be natural, unobtrusive, and in keeping with the subject. In order to achieve this effect many photographers use the light that is available…As emulsions become faster, lighting equipment for the photojournalist becomes smaller and less powerful.” I can’t begin to imagine what he would think about the current crop of digital cameras can do. He is right about the lighting becoming less powerful (as compared to larger studio strobes) as film becomes faster.

When discussing the potentialities for the future, in terms of different ways still photography can be presented, David Douglas Duncan’s work from the 1968 political conventions which was shown on NBC and eventually turned into the book Self Portrait USA is mentioned. Rothstein see this as a possibly a new way of using still images on television. Duncan seemed to be at the forefront of multimedia storytelling, without the infrastructure to support it.

At the end of the book there are summarizing questions for each chapter at the end and some practical exercises. This is something that will be seen in other textbooks. Placing them all at the end does require some flipping back and forth. When the questions are directly after the chapter, they are more effective.

What is my take away from this book? For the time period, it is good. Going through it now is an act of nostalgia for a time I never lived through. His overall points about photojournalism being a form a communication is solid and worthwhile is 2023. The current market is different today. It is good to know the history of photojournalism beyond the established Time/Life canon and Weegee. Rothstein structured his book in a way that has been used in later books. His writing and examples are clear and concise.

There is one place where more explanation would have been helpful, mainly law and ethics. He uses historical events mostly related to cameras in courtrooms. (There was no CourtTV in 1974). Copyright and ownership are also covered. Each topic gets a paragraph or two. These topics, while necessary, are rarely fully discussed in a book of this length (224 pages).

I had known of Rothstein as the person who made the dust storm and cow skull FSA pictures (see above), but for little else. By the time I was journalism school he had been dead for a few years. My focus was more on newspapers than anything else, except for W. Eugene Smith, who I was obsessed with. Going through this book, I have gained a greater understanding of Rothstein and his approach to the medium of photojournalism. He also wrote a book about documentary photography which will be the subject of an upcoming newsletter, and in his mind photojournalism and documentary photography are two different things. In today’s world, the line between the two is blurrier. The line was clearer when Rothstein wrote this book.

When it comes to the example photographs, news photographs are represented heavily by the wire services of the day. Feature photographs mostly come from Look magazine. Rothstein again draws a line between news and feature pictures. I have always admired the direct statements of wire service photography. I have also found it difficult for me to consistently make pictures that fit within the confines of photojournalism definition written by the wires. I appreciate those who are able to do it well. This notion of photojournalism is alive within the wires today.

Current photographers who make work that is communicative and goes beyond the “right is tight” mentality, include Natacha Pisarenko, Rodrigo Abd, and Damir Sagolj. What I see Spencer Platt doing for Getty Images is also interesting. David Guttenfelder, who started with the AP and has gone beyond the label of a “wire photographer”. I see a difference in the kinds of work from the non-America wire photographer compared to Eric Gay who is based in Texas. His work is excellent and more in-line with being a traditional American wire service photographer. I see US based wire service photographers being focused on news and sports events, not necessarily photo essays, but I am simplifying things with this thinking.

Had I read this book during my college years would my attitudes about photojournalism have changed? I doubt it. I have always bristled at severe cropping (those feelings were at the surface when I saw the white rectangles on the photos in the above example). I learned and worked for a few of the more old-school editors. I tended to clash with them too. If I had been willing to take direction a bit better in my younger years, I would have been better off. If I am being honest, making clean tight communicative pictures is not easy. My solution to this problem of not being able to make those pictures was to stand back a bit and make a subtler picture. I leaned toward feature side of journalism. Distance, perspective, and this book have helped me see this.